Marta Estrada and her 12-year-old son carry water from a cistern on the ground floor of their building to their apartment on the third floor. Ronald came home from school and took off his uniform to help his mother with a small bucket. They go up and down more than ten times until they manage to fill the 50 liter tank in the bathroom and another 200 liter one in the kitchen. They live alone in the Buena Vista neighborhood in Las Tunas, one of the driest provinces in Cuba.

“Water has never reached the shower in the bathroom, but it used to make it to the kitchen, and we’d be able to fill the tank with a hose. Now, there isn’t enough pressure to get it up here when they “put it on” every three days,” Marta laments.

Having recovered from fatigue and exhaustion, they both look out from their balcony at the dust and dry trees that stand on both sides of Antonio Barrera Street. Scarce rainfall in the area has created a “complex” landscape, that’s how the Las Tunas provincial government refers to the drought.

However, this isn’t one of the hardest-hit areas. There isn’t even ground water up in the north of the province, especially in the Manati municipality. A total of 6,500 inhabitants (out of a population just over 30,000) are directly affected by this absence of rain – a longstanding “natural whim”.

Even though Las Tunas Government says that “sound investments” are being made to prioritize water supply to the population, shortages haven’t just been a problem in 2023, there’s been a crisis for years now.

Rainfall has fallen below 85% of forecasts, for a decade. With drought extending over such a long period of time, accumulated precipitation levels are becoming more and more depleted. Up until early February 2023, the 23 dams in the province had only collected 30% of their total capacity. This problem goes hand-in-hand with fuel shortages that don’t allow for using the train to be regularly used to carry water to places that need the vital liquid.

“Weevil” training course

When the water supply situation gets tense in Cuba, you often hear the phrase “I’m doing a weevil training course.” Those insects that don’t need water to survive and are mentioned by Cubans to describe the problems they face when there is water scarcity.

Drought in Cuba has increased over the past 30 years and things aren’t looking promising in 2023 either. It’s expected that the dry season will last until after April, which will mean more people will be affected by the water supply. This is what the director of Hydrology and Hydrogeology at the National Institute of Hydraulic Resources (INRH), Argelio Fernandez announced.

In early March 2023, over 400,000 people were affected by the scarce water supply as a result of drought and hydraulic works.

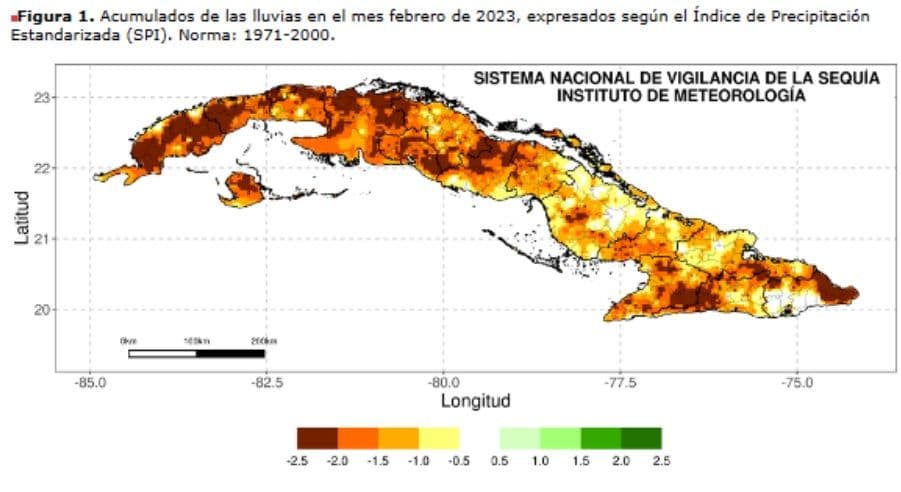

According to the weather institute (INSMET), February 2023 ended with “94% of the country with a deficit in accumulated precipitation. Out of the country’s 168 municipalities, 145 recorded a moderate to extreme deficit in over 25% of its regions. Out of those, 130 had over 50%, 112 with over 75% and 58% with 100% of their areas affected.”

In terms of accumulated precipitation, 50% of Cuba fell under the severe – extreme category, 27% under moderate and 17% under weak.

The provinces in the worst situation because of scarce rainfall are Guantanamo (over 94,000 people affected), Camaguey (over 60,000), Santiago de Cuba (over 50,000), Havana (over 47,000) and Holguin (over 150,000).

Water systems operated by INRH supplying water to 2,416 urban and rural settlements (8,240,000 inhabitants).

Some 900,000 people are supplied by MINAG and AZCUBA.

Nearly a million people are supplied by water tanker trucks, on a permanent basis.

800,000 need to carry it 200-300 meters to their home.

Source: National water policy

It’s not even clean water

Drought isn’t the only water-related issue in Cuba. The poor quality of this liquid is also a problem in many places across the country. According to statistics from the National Water Policy, 3.1 million people are drinking untreated water.

For example, in Santa Clara, the poor quality of water has been a constant problem, especially on days when it rains. There, religious institutions such as the Diocese or state-led water-treament plants often offer the population drinking water so they can fill bottles and other containers. Even selling water and ice, or donations of purified water, were a business or economic enterprise for some residents, over a long period of time.

In May 2022, many residents in the city center – especially those with small children and sick relatives – complained on social media about water being sold by the company Los Portales LLC., in the US dollar magnetic convertible currency called MLC.

“That was the last thing we needed,” the mother of a two-year-old boy said. “Water was the only thing left in stores selling in Cuban pesos and then they were also selling 5-liter bottles in foreign currency.”

At that time, government authorities resonded that Los Portales LLC. had distribution problems so they wouldn’t be able to supply retail stores. However, shortages of water at peso stores – and sometimes even at MLC stores – has led to long lines early in the morning from the break of dawn. A 1.5 liter bottle of natural mineral water can cost up to 400 pesos on the illicit market. That’s nearly 20% of a monthly minimum wage.

The drinking quality of water isn’t the only problem with water in Villa Clara. In early 2023, the region reported over 98,000 people without access to water because of faults in pumping equipment. The municipalities with the most problems are Camajuani, Santa Clara, Ranchuelo and Manicaragua, where water used to be transported in tanker trunks depending on availability of fuel.

Vladimir Santaya Santana, director of the Water and Sewage Company in the province, said that the definitive solution to this repetitive crisis with water supply would come once pumping and purification equipment of Villa Clara’s main systems are replaced – an investment which the Government hasn’t contemplated up until now.

Meanwhile, Cienfuegos locals are “privileged” for having water on alternate days. It might seem like a joke, but it isn’t. Right now, access to water one day yes and one day no is “quality of life,” as the first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) in the province, Maride Fernandez Lopez, called it during a meeting with residents.

“We, the people from Cienfuegos, are privileged to have water one day yes and one day no. There are other provinces where water supply systems take 15 days, a month and even three months,” Fernandez Lopez said. “But we in Cienfuegos have to continue to try and keep access to water one day yes and one day no because this is quality of life.”

The Manuel Tames municipality in Guantanamo is one of the places where drinking water only comes every 25 to 35 days via the network or water tanker trucks. Seven thousand people are suffering the drought, while 95,000 people in this eastern province have been affected.

Drought brings profits for opportunists

A report on Cuban TV recently cast a light on the water scarcity situation in the archipelago, low availability of water in dams, the losses in distribution networks, problems with purification, equipment and pipes, and a transport deficit for the tanker truck service.

The intermittent operations of vehicles owned by Aguas Santiago and Aguas Turquino in Santiago de Cuba has been a problem since April 2022, for example. Statistics published in Juventud Rebelde reveal that demand appearing in 47 thirsty urban neighborhoods are competing with 240 communities that don’t have a water supply network and receive their water from water tanker trucks in the province.

Thousands of people “depend on an outdated method, with trucks breaking down and in need of spare parts that don’t exist. This means that water only comes in after four weeks, which has been as long as three and four months in communities such as Las Guasimas and El Sapo. The situation has become more tense in hard-to-reach areas Guama, Tercer Frente and San Luis, where special means are needed or four-wheel drives are needed to transport the liquid, the document reads.

There are also irregularities in the fleet of tanker trucks in Guantanamo, fuel shortages and a deficit of tires and batteries, as well as leaks which can’t be fixed because lead needed to solder the pipes is in shortage. The hardest hit municipality today is Maisi, which has zero access to all of its supply sources.

Likewise, in Sancti Spiritus, where actions taken to alleviate the situation have been to adjust pumping operations to one day for Cabaiguan and two days for the provincial capital, as well as moving water tanker trucks to communities affected.

Quickly searching in Revolico groups on Facebook, you can find ads of people wonder where there are water pumps, tanks, filters, etc.

February 2023 was the month with the least rain in Matanzas in the past 42 years. Photo: elTOQUE

Ads for selling plastic water tanks are also frequent, with a capacity of 800, 3,000 and 5,000 liters, and can be installed at home, which people can pay for in MLC, pesos, or via the Zelle electronic payment system (based in the US). Prices range between 37,000 to 100,000 pesos.

Drought has forced people to find alternatives to alleviate the tense situation, while others have taken advantage and banked on the situation.

In a comment to an articles published in Escambray, a user identified as Julia says that “water sellers are pestering people in Trinidad, the parade of water tanker trucks in a show in the town and they charge up to 600 pesos for every trip that only gives you enough to shower and cook, but where does this water come from? Nobody has a private well here. This is an everyday occurrence, and everyone sees it happening.”

The user also complained about investments and repairs in the hydraulic sector, which she called “shoddy work”. She said that there isn’t any real quality to the work and that new pipes leaking is “an embarrassment”.

Lots of the time, the authorities complain about people breaking pipes to redirect water to their homes.

Marta Estrada remembers that near the Maximo Gomez high school where her son Ronaldo studies, she saw a water tanker directly filling up a tank in a home. “The school doesn’t have water in the bathrooms and the water tanker is just a few meters away supplying a residence,” she says.

Then, some of her son’s classmates told her that it was the home of a director in the sugar industry.

In late 2021, buying a tanker of water “illegally” cost between 400 and 600 pesos. A year later, this price now stands at more than 3,000 and, in lots of cases (as what happens with most highly valued products), water is sold to the highest bidder.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *