Going over what has now come to be called the Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara case seems redundant by now. But, it’s not like that in a country like Cuba, where ordinary citizens don’t know about basic laws and their fundamental rights and this leads them to being in a state of socio-political inertia which works based on the principle of a spiral of silence.

This is what makes the #00 Biennial that Luis Manuel and a group of Cuban artivists want to hold in May 2018 a hair-chilling roar to “our political-cultural jungle”. If the slightest raising of voices is uncomfortable for Cuban authorities, just imagine what a loud cry is.

From their own slogan: From official to unscrupulous, these artists are coming out, going against the tide and are almost showing that their work moves along the line between art and political activism.

Luis Manuel has been the tip of the iceberg of many dispersed pieces of ice. Graffiti and performance artists know this better than anyone else because they take over public spaces and “damage social property” on the island.

Fabian Lopez Hernandez, known as 2+2=5, is a young man with a curly afro who slides along Havana’s streets on a skateboard and, when the sun goes into hiding, he graffitis the city’s grey corners, walls that are about to collapse because, as he himself says, he wants to express what he feels and show society the things that aren’t right.

He paints the marginalized, who transmit a lack of care and hope. When I ask him if he makes resistance art consciously, he answers, “yes, of course I do.”

“Resistance against what, who?” I ask again.

“Against people’s needs and social problems. Not against a person.”

“Is your discourse local or do you want it to speak to a more universal society?”

“It’s for the Cuban people, because I speak about my experiences here in Cuba.”

“Do you think your art relates to the art made by other Cubans from different generations, or does it belong more to an artistic movement of today’s resistance?”

“I believe that artists have risen up with the same intention, but I don’t belong to any arts movement because I do what I do on my own and it comes from me.”

Fabian tells me that he has received fines and been taken to the police station for “doing what he does”. “1000 peso fines and up to a week at the police station,” he says, “using damage to social property as an excuse.”

Yulier P’s case is similar to Fabian’s; Yulier P is another graffiti artist who has taken over the capital’s streets, whose videos even go around via the Weekly Package. Recently, he became famous for his arrest and detention for several days.

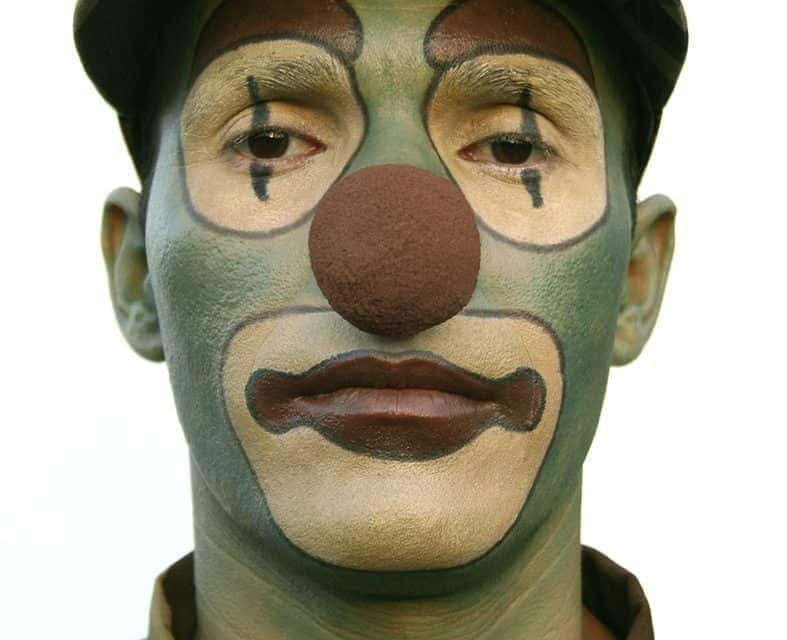

Yoanny Aldaya is another artist who seems to be obsessed with his body (more nude than wearing clothes) if you look at his photographic work and performance pieces.

Gestures, transpositioning parts of his body with objects, the nude as a psychological blow and the expressive force of the dark and sometimes grotesque prevail throughout this young man from Old Havana’s art who, last year, decided to take the star-spangled banner after US-Cuban relations were reestablished and lash his back with it, in a public setting, while he held a McDonalds with his free hand and ate it.

“I wanted to do this in front of the Capitolio in the days leading up to Obama’s visit, but I didn’t because it could have been manipulated and given a more political meaning; it’s a more social piece for me and has more to do with the ordinary Cuban person’s way of thinking, which is that they believe that things are going to change when really there might not be any changes. I’m not interested in making noise, but in showing how the ordinary Cuban has created this idea of change, a new concept of “Yankeeism” and I compared this US symbol with the Cuban one and that’s how the performance (The past is the future) was born, which speaks about consumerism and how it makes you a slave of what you consume. I presented it at a performance arts festival that was held in Mayabeque,” he tells me.

Now that relations between both countries have rolled back, it seems that Yoanny Aldaya was right. Especially because he’s one of the people who believes that “art is to question things and that if you live in a world and you don’t criticize the things that are bad socially and politically, what’s the use of being an artist? Why are you going to paint a picture to just hang it up on your wall at home? I don’t have anything against aesthetic pleasure, but the concept of the piece overrides aesthetic, and this concept stems from social or political issues,” he states.

Yoanny during the performance. Photo:Courtesy of the interviewee

A generation older than Yulier, Yoanny, Luis Manuel or Fabian, another artist like Adonis Flores believes that “there are people who work very directly, so sharply that they move away from art and fall into mere activism. I’m not referring to artivism, where Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has stood out with his work, but political activism.”

Here in Cuba, Adonis names the ‘80s Generation as the antecedent to the younger generation today. “A lot of Tania Bruguera’s generation, over 40 years old, have left. The same thing has happened with many young artists, who have left the country and are unable to carry the same discourse outside of Cuba because their work won’t receive the same attention and people abroad won’t exactly know what is happening here. They lose their direct contact and become more removed from politics and what is happening in Cuba.”

Nevertheless, those who stay look for alternative ways to exhibit their work. For example, the Nada Personal (Nothing personal) exhibition (November 7-23, 2017, which was exhibited at a home on Espada and San Lazaro streets) which brought artists such as Dany del Pino, Javier Bobadilla, Jose Ernesto Alonso, Luis Manuel Otero, Yoanny Aldaya, Yuri Obregon and Ranfis (the collector of absurd facts which are exhibited on the Cuban Art Factory mural: 1959, the last year of hunger) together. With regard to Nada Personal, critic Angel Perez said that “it’s a political essay; the projection of a break with the paradigms that modeled Cuban ideology after the epic 1959 victory.”

This open attitude of questioning paradigms is creating more and more friction between young artists and Cuban authorities. And every one of the people interviewed in this article has their own incident to tell. For example, Adonis Flores, who for acting in a public space, was asked to show his ID card, but he wasn’t arrested.

Carne de Canon piece by Adonis Flores. Photo: Courtesy of the interviewee

“I’m interested in polysemy, in dialogue. If you directly point to something, you nearly become an activist. The opportunity to create a dialogue is lost, you’re just pointing something political out,” he explains. “Sometimes, I ask myself: what’s the point of doing politically direct things, to create your art or to make them arrest you so that you become relevant and get free publicity?”

Adonis knows from his experience that art in Cuba has become institutionalized via a cultural policy that leaves very little space for alternative art. Every artist who has read Fidel’s early words in his “Words to Intellectuals” knows this: “Within the Revolution, everything; outside of the Revolution, nothing.” Both Cuban film and theater have a long history of being regulated which leaves out everything that doesn’t go along the government’s “Leftist” line. We aren’t in the Five Grey Years or Special Period, but political powers continue to influence (if not determine) Cuban art.

This article was translated by Havana Times from the original published in Spanish.