It’d only been an hour since the multimedia special “Migration: a life or death situation” went live that the first report reached El Toque’s inbox ([email protected]). It was 9:20 AM on February 28, 2023 and a sentence made my blood chill: “I have two cousins who have disappeared.” I was ready for it, but sorority is strong in me.

A month after it was published, this journalism project has proven to be useful and a source of hope for families who remain in a limbo as to the whereabouts of their loved ones and aren’t receiving support from the Cuban government to search for the disappeared.

The number of Cubans who have passed away or gone missing since they’ve left the country to head towards the United States has risen.

When the multimedia special went live, we had 733 records of migration incidents that took place on different routes from Cuba to the U.S.; including disappearances, deaths, rescues, transfers, repatriations and deportations. Out of these, there were at least 98 deaths and 340 disappearances, of which only the identity of 60 and 184 people were confirmed, respectively.

There are now 772 migration incidents, 119 deaths and 393 people missing. We have been able to give a face and name to a total of 79 fatalities and 248 people whose whereabouts remain unknown.

“Thank you. I will always be grateful for any help you can give me, as I haven’t received any support from authorities in this country, not to mention the Ministry of Interior which is responsible for searching for them. They couldn’t care less. As I’m just a teacher and not a leader, this isn’t important for them,” a mother tells me who has been looking for her son since July 26, 2020.

The young man left his home that night and never came back. Even though he confessed he was afraid to embark on this journey to the US by sea, his mother says he was crazy about leaving the country. There are many stories like this. There are many mothers who suffer because they don’t know where their sons and daughters are, and there are dozens of broken families.

“My son left on May 25, 2021 and a boat sunk on the 27th. Eight were rescued, two bodies were found and ten people went missing. I’ve been searching for news of him and the other young people on that boat ever since,” a mother tells me via the platform. I can feel her pain and helplessness. I tell her she’s not alone. That I share her nostalgia. That we want to accompany her in this disturbing time and facilitate any information that we can possibly uncover.

It had only been three days since February 28th when I received a notification in my personal email from an unknown sender. A mother had found out how to contact me.

The mother explained that her son had left Cuba on a boat on December 23, 2022. A source – without going into details – had told her family that the migrants handed themselves over to authorities on January 26, 2023 and were then taken to the Bahamas. She hasn’t heard anything about their whereabouts or details of their situation since. Thanks to this Cuban, we were able to identify 15 migrants whose names hadn’t been registered up until then.

Days later, the executive director of Cuba Archive, Maria C. Werlau, sent us her list of deceased Cuban migrants, whose identities had been meticulously collected by the project. Thanks to this collaboration, we were able to add 14 migration incidents to our records and 15 fatalities.

Strategies to track information aren’t only limited to family members contacting us via the platform, though. We have also posted in different Facebook groups, contacted relatives who comment that they are looking for someone or are sad about their loss on social media. We go to great lengths to disseminate the journalism special and victims’ families take it on as theres.

“Hello, how are you? I’m sorry for writing to you,” an acquaintance writes to me on Messenger.

I always drop whatever it is I’m doing when I receive a message. The people writing to me are my top priority. I’ve never felt so useful or carried such a heavy burden. It makes me remember my PhD thesis director when she’d stress to me for two years: “They aren’t numbers Loraine, they’re lives.”

“I saw a post on a page where you can put the name of people gone missing on their journey. I added the details of my husband’s cousin and put in my email and phone number, but I’m not sure I did it properly,” she explains in the chat.

Every case is painful to hear, but the fear always grows when faces start becoming familiar. I feel like one day someone from my family or a friend could be on the list. Just thinking about it makes me shiver. Even though I know that this feeling is nothing compared to what victims’ families must be feeling.

I ask for information, one by one, to complete the record. It’s the same story over and over again: young people looking for a future. “We just have to wait and have faith,” she tells me before saying goodbye.

Moments later, the sister of two people gone missing confesses: “it’s really hard to go through this situation and not know what you can possibly do.” I always remind them that they aren’t alone, that we want to support them and we are looking for a way to do this. “That’s good to know,” she tells me and I feel goosebumps all over my body. I can sense an desolation in her words.

Victims’ families have suffered a great deal. In addition to their loss and distress, there are attempts at extortion – especially from Mexico. Criminals try to make money off giving fake information about the whereabouts of the missing. This makes our dialogue even harder when people ask me – in an attempt of self-defense – where I live, which is Mexico. Luckily, they give me a chance to confirm my identity and they go to the database.

Other channels (such as Messenger and WhatsApp) have allowed us to add new cases and update or correct preexisting records. This is why we need users to help us share, visibilize and amplify the reach of this special.

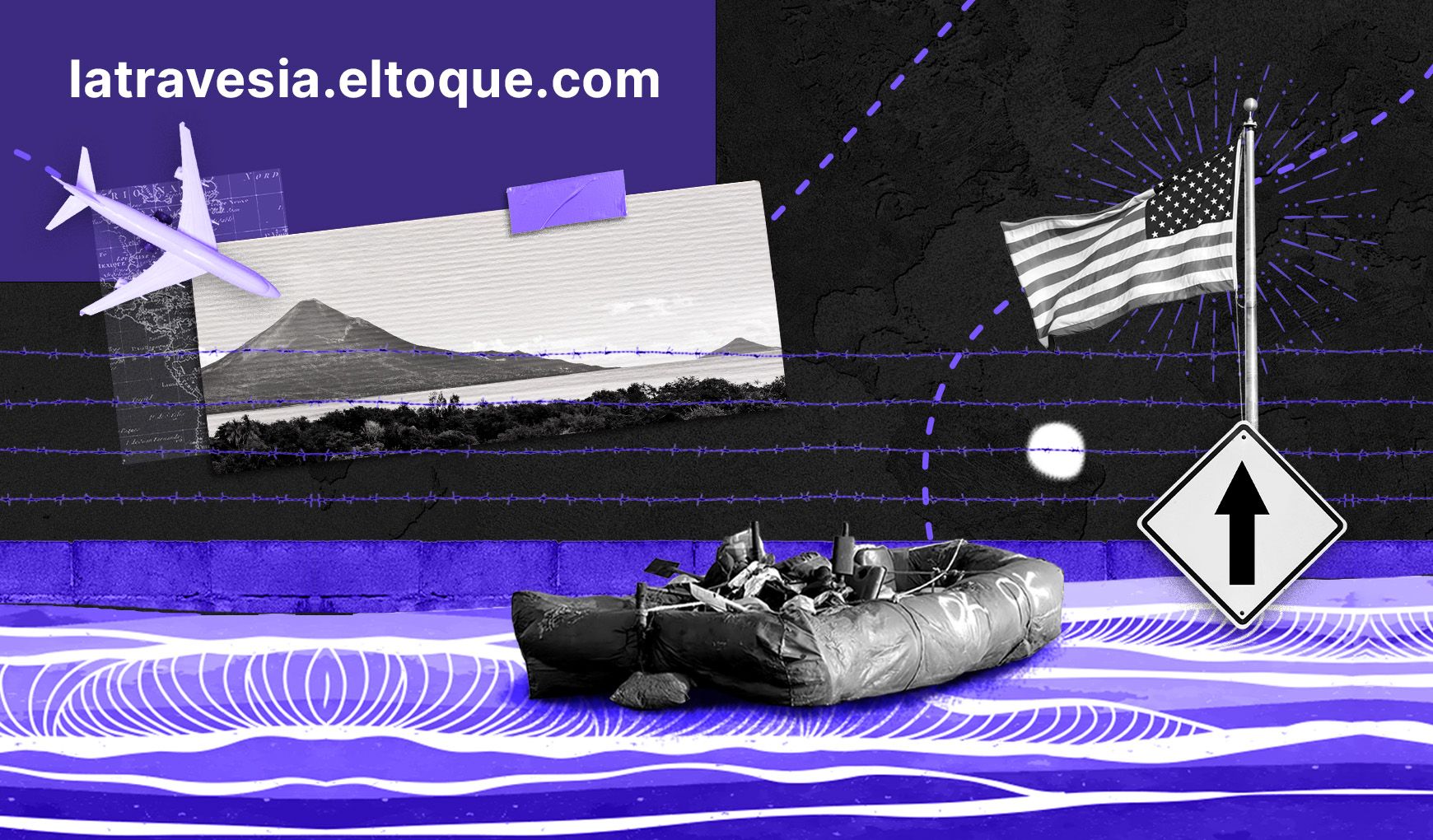

The journey, which is also the name of this journalism project, is the first record of tragic events of Cubans along migration routes. Thus the importance for it to continue and grow, because it is a tool of social memory and has information that allows us to put group pressure on the corresponding bodies about a key issue for Cuban society today. It’s also an updated register for when politicians decide to give in, take action and join the search for the missing; and it’s also a memorial to try and stop those who are no longer with us from being forgotten.

Exodus is always political. That’s why the blood of those who have become victims in their departure and search for new lands is on the Cuban State’s shoulders, because it was denied to them in their own country.

—–

*Names were not mentioned as this El Toque service guarantees identity protection for those who report to us.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *